Muscular Torticollis: A Comprehensive Guide

What It Is

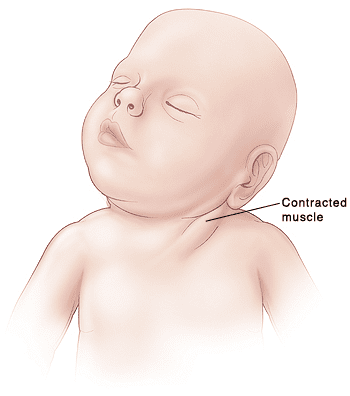

Muscular torticollis, also known as congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) when present in infants, is a condition characterized by a shortened, tightened sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle in the neck. This causes the head to tilt down and toward the affected side (ipsilateral tilt) and rotate up and toward the opposite side (contralateral rotation). It is the most common type of torticollis and is often identified in infants within the first few weeks or months of life.

Types

Torticollis is generally categorized by its cause and timing:

- Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT): Present at or shortly after birth. It is the most common form.

- Acquired Muscular Torticollis: Develops later due to an event or condition. Subtypes include:

- Postural Torticollis: Related to habitual positioning or environmental factors (e.g., always sleeping on one side, prolonged time in car seats).

- Traumatic Torticollis: Caused by injury to the SCM muscle or cervical spine.

- Paroxysmal Torticollis of Infancy: A rare, benign condition involving recurrent episodes of head tilting, often associated with vomiting and irritability, which resolves spontaneously.

It’s crucial to distinguish muscular torticollis from other, more serious causes of a tilted head, which are non-muscular and may be due to bone abnormalities (e.g., Klippel-Feil syndrome), vision problems (ocular torticollis), or neurological issues.

Symptoms

The signs are usually visible and consistent:

- Head Tilt: The head is consistently tilted toward one shoulder.

- Chin Rotation: The chin is rotated upward toward the opposite shoulder.

- Limited Range of Motion: Inability to turn the head fully in both directions.

- Palpable Neck Mass: In approximately 10-20% of infants, a small, firm lump (a fibrotic mass or “pseudotumor”) can be felt in the tightened SCM muscle. This usually resolves with treatment.

- Plagiocephaly: Flattening on one side of the head (positional plagiocephaly) due to always sleeping in the same position.

- Asymmetrical Facial Features: In more severe or untreated cases, facial asymmetry may develop.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is primarily clinical:

- Physical Examination: A pediatrician or specialist will observe the infant’s head position and neck movement. They will attempt passive stretching to assess the muscle’s tightness and rule out other causes.

- Ultrasound: Often used to visualize the SCM muscle and confirm the presence of a fibrotic mass or muscle thickening. It is painless and radiation-free.

- X-ray or MRI: These are not typically needed for uncomplicated muscular torticollis. They are only ordered if the doctor suspects an underlying bone abnormality (like atlanto-axial rotary subluxation) or neurological issue, especially if the physical exam is atypical.

Prevention

There is no sure way to prevent congenital muscular torticollis, as its exact cause is often unknown (possibly due to crowding in the womb or birth trauma). However, preventing the secondary complications is key:

- Supervised “Tummy Time”: As soon as a doctor approves it after birth, frequent tummy time while the baby is awake helps strengthen neck and shoulder muscles and prevents plagiocephaly.

- Alternating Positions: Alternating the direction the infant’s head faces when putting them down to sleep (once they can roll over safely, always place them on their back to sleep) and alternating holding and feeding positions.

Treatment

The goal is to stretch the shortened muscle to restore full, pain-free range of motion.

- Conservative Management (First-Line, >90% success rate):

- Physical Therapy: The cornerstone of treatment. A therapist teaches parents passive stretching and positioning exercises to perform at home multiple times a day.

- Positioning and Environmental Strategies: Encouraging the child to actively turn their head toward the affected side by placing toys, lights, and engaging with them from that direction.

- Tummy Time: Crucial for strengthening the weak opposite neck muscles.

- More Advanced Interventions:

- Botulinum Toxin (Botox) Injections: Occasionally used in persistent cases where therapy has plateaued. It temporarily weakens the tight muscle to allow for more effective stretching.

Types of Surgery

Surgery is rarely needed (less than 10% of cases) and is only considered after at least 6-12 months of failed intensive physical therapy, usually in children over 12 months old.

- SCM Release Procedures: The goal is to lengthen the tight muscle. The two main techniques are:

- Unipolar Release: Cutting the lower attachment of the SCM muscle (near the clavicle).

- Bipolar Release: Cutting both the upper (mastoid process) and lower attachments of the muscle. This is done for more severe cases.

- Post-surgery, physical therapy is essential to maintain the gained range of motion.

Prognosis

The prognosis for muscular torticollis is excellent.

- Over 90% of cases resolve completely with conservative physical therapy and home exercises, especially when started early (before 6 months of age).

- Early treatment leads to the best outcomes and prevents complications like plagiocephaly and facial asymmetry.

- Even cases requiring surgery have very good outcomes when followed by proper rehabilitation.

Warning Signs & When to See a Doctor

Consult a pediatrician immediately if you notice:

- A consistent head tilt or limited neck movement in your infant.

- A lump in your infant’s neck.

- Flattening developing on one side of the baby’s head.

- Red Flags (suggesting non-muscular causes): Sudden onset of torticollis, associated fever, difficulty swallowing, drooling, slurred speech, weakness in limbs, or signs of trauma. These require immediate medical attention.