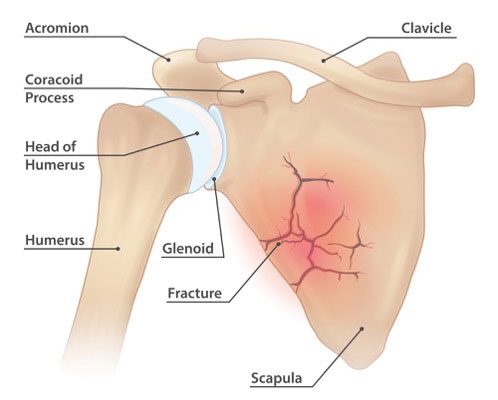

Scapula Fractures: A Comprehensive Guide

What it is:

A scapula fracture is a break in the shoulder blade (scapula), the large, triangular bone that connects the upper arm (humerus) to the collarbone (clavicle) and forms the back of the shoulder girdle. These are rare fractures, accounting for less than 1% of all broken bones and only 3-5% of shoulder girdle injuries. Their rarity is due to the scapula’s protected position, surrounded by thick muscles and located on the mobile and resilient thoracic cage. Because it takes a significant amount of force to break it, a scapula fracture is often considered a “high-energy trauma” injury.

Types:

Scapula fractures are classified by the specific part of the bone that is broken:

- Body Fractures: The most common type, involving the main flat body of the scapula.

- Glenoid Fractures: The glenoid is the socket part of the ball-and-socket shoulder joint. Fractures here can affect joint stability.

- Acromion Fractures: The acromion is the bony roof of the shoulder. A break here can impinge on the rotator cuff tendons beneath it.

- Coracoid Process Fractures: The coracoid process is a hook-like bone where ligaments and tendons attach. Isolated fractures here are uncommon.

- Scapular Neck Fractures: This involves the narrow section between the head (glenoid) and the body. Severe displacement can affect shoulder mechanics.

Symptoms:

- Severe pain in the shoulder and upper back, worsened by any attempt to move the arm or shoulder.

- Significant swelling and bruising around the back of the shoulder, which may appear days later.

- Holding the arm close to the body in a protective posture.

- A visible deformity or flattening of the normal shoulder contour in severe, displaced fractures.

- Painful grinding sensation (crepitus) with minimal movement.

Diagnosis:

- Physical Examination: A doctor will look for swelling, bruising, and deformity. They will perform a thorough neurovascular exam to check for associated injuries to the arm’s nerves and blood vessels, which is critical.

- X-rays: Standard shoulder X-rays, including specialized views like a “Y-view,” are the first step to identify the fracture.

- CT Scan: This is the gold standard for diagnosing scapula fractures. It provides detailed 3D images that are essential for understanding the fracture’s pattern, displacement, and involvement of the shoulder joint (glenoid), which is crucial for surgical planning.

Prevention:

Prevention focuses on avoiding high-energy trauma:

- Always wear a seatbelt in a vehicle.

- Wear appropriate protective gear for high-impact sports (e.g., football, motocross) and occupational hazards.

- Practice safety measures to prevent falls from significant heights.

Treatment:

- Non-Surgical Treatment: The majority of scapula fractures are treated non-surgically because many are non-displaced or minimally displaced and heal well with immobilization.

- Sling or Shoulder Immobilizer: Worn for 3-4 weeks to support the arm and minimize pain.

- Medication: Pain management with NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen) or acetaminophen.

- Physical Therapy: Begins early with gentle pendulum exercises to prevent shoulder stiffness, progressing to active motion and strengthening as healing permits (usually around 4-6 weeks).

- Surgical Treatment: Surgery is reserved for fractures with specific patterns that are likely to lead to poor outcomes without intervention. Indications include:

- Intra-articular Involvement: Fractures where the glenoid socket is disrupted and the joint surface is misaligned (“step-off”).

- Severe Displacement: Fractures of the neck or body where the pieces are significantly out of place, which can alter shoulder mechanics.

- “Floating Shoulder”: A combined fracture of the scapular neck and the clavicle, which creates severe instability in the shoulder girdle.

Types of Surgeries:

- Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF): This is the standard procedure.

- The surgeon makes an incision, carefully moves muscles aside to access the bone, repositions (reduces) the fracture fragments into their normal alignment, and secures them with metal hardware.

- Plates and Screws: Specialized contoured plates are applied along the borders of the scapula (e.g., along the posterior border or the spine of the scapula) and held with screws. This provides stable fixation to allow for early motion.

Prognosis:

- Non-Surgical: Most patients with non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures have an excellent prognosis. They typically regain full or nearly full shoulder function after a course of physical therapy, though some may have occasional aches.

- Surgical: With modern surgical techniques, outcomes are generally very good. The goal is to restore normal anatomy to prevent long-term pain, weakness, and arthritis. Recovery involves a period of immobilization followed by a strict and prolonged physical therapy protocol. Full recovery can take 6 months to a year.

- Potential Complications: Include shoulder stiffness (most common), post-traumatic arthritis (if the joint surface was involved), hardware irritation, and, rarely, nerve injury or nonunion.

Warning Signs & When to See a Doctor:

Due to the high-energy nature of these injuries, they are often accompanied by other serious damage. Any significant trauma to the shoulder that causes severe pain and inability to move the arm requires immediate medical evaluation in an emergency room.

Go to the Emergency Room immediately. Additionally, be aware of these red flags that suggest associated life-threatening injuries:

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing (could indicate a punctured lung or rib fractures).

- Numbness, tingling, or weakness in the arm or hand (sign of nerve injury, often to the brachial plexus).

- The arm or hand feels cold, pale, or has no pulse (sign of vascular injury).