What is this?

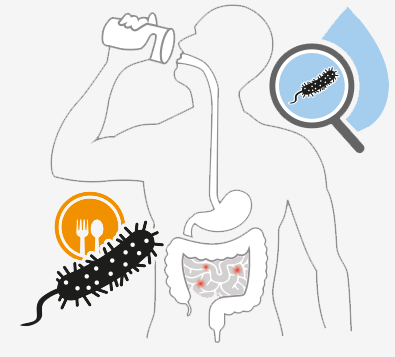

Cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by consuming food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae

Risk factors

Everyone is susceptible to cholera, with the exception of infants who get immunity from nursing mothers who have previously had cholera.

- Poor sanitary conditions. Cholera is more likely to flourish in situations where a sanitary environment — including a safe water supply — is difficult to maintain. Such conditions are common to refugee camps, impoverished countries, and areas afflicted by famine, war or natural disasters.

- Reduced or nonexistent stomach acid. Cholera bacteria can’t survive in an acidic environment, and ordinary stomach acid often serves as a defense against infection. But people with low levels of stomach acid — such as children, older adults, and people who take antacids, H-2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors — lack this protection, so they’re at greater risk of cholera.

- Household exposure. You’re at increased risk of cholera if you live with someone who has the disease.

- Type O blood. For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, people with type O blood are twice as likely to develop cholera compared with people with other blood types.

- Raw or undercooked shellfish. Although industrialized nations no longer have large-scale cholera outbreaks, eating shellfish from waters known to harbor the bacteria greatly increases your risk.

Symptoms

Most people exposed to the cholera bacterium (Vibrio cholerae) don’t become ill and don’t know they’ve been infected. But because they shed cholera bacteria in their stool for seven to 14 days, they can still infect others through contaminated water.

Symptoms of cholera infection can include:

- Diarrhea. Cholera-related diarrhea comes on suddenly and can quickly cause dangerous fluid loss — as much as a quart (about 1 liter) an hour. Diarrhea due to cholera often has a pale, milky appearance that resembles water in which rice has been rinsed.

- Nausea and vomiting. Vomiting occurs especially in the early stages of cholera and can last for hours.

- Dehydration. Dehydration can develop within hours after cholera symptoms start and range from mild to severe. A loss of 10% or more of body weight indicates severe dehydration.Signs and symptoms of cholera dehydration include irritability, fatigue, sunken eyes, a dry mouth, extreme thirst, dry and shriveled skin that’s slow to bounce back when pinched into a fold, little or no urinating, low blood pressure, and an irregular heartbeat.

Dehydration can lead to a rapid loss of minerals in your blood that maintain the balance of fluids in your body. This is called an electrolyte imbalance.

Electrolyte imbalance

An electrolyte imbalance can lead to serious signs and symptoms such as:

- Muscle cramps. These result from the rapid loss of salts such as sodium, chloride and potassium.

- Shock. This is one of the most serious complications of dehydration. It occurs when low blood volume causes a drop in blood pressure and a drop in the amount of oxygen in your body. If untreated, severe hypovolemic shock can cause death in minutes.

Cholera Complications

- Hypoglycemia. If you can’t eat because of the stomach pain and vomiting that comes with cholera, your blood sugar may drop too low. Low blood sugar can cause symptoms like seizures, passing out, and even death, if it is severe enough. Children with cholera are more likely to have low blood sugar than adults.

- Low potassium. When you have diarrhea, you can lose important minerals, like potassium, in your stool. When potassium levels get too low, it can impact your heart and nerves.

- Kidney failure. Damage to your kidneys can make them lose their ability to filter. This can cause fluid, waste, and electrolytes to build up in your body. This can be life-threatening and often happens along with shock if you have cholera.

Treatment

- Rehydration therapy

- Antibiotics

- Zinc supplementation for children

Prevention

People traveling from the United States to areas affected by cholera can get a cholera vaccine called Vaxchora. It’s suggested for people between ages 2 and 64 who plan to travel where cholera is being spread or regularly spreads. It is a liquid dose taken by mouth at least 10 days before travel.